Ok, I'm breaking my usual rules twice in as many weeks. But when you get interesting news like this, it's hard to resist. By now everyone is aware that "Putin's Plan" has been (at least partially) revealed: Putin will head up the United Russia party list in the December 2007 Duma Elections and will likely be appointed Prime Minister by his successor, who is assumed to be the current Prime Minister, Zubkov.

Lyndon at Scraps of Moscow relayed an interesting analysis from an expert on a panel he attended in his post on the subject:

In any event, it's amazing how quickly the March 2008 presidential elections have come to seem irrelevant. Today I attended a panel discussion which was not focused on the presidential succession question, but the news had to be discussed. One of the participants, a leading scholar of Russian politics visiting from Moscow, suggested that this must have been the first discussion in DC of the new reality of Russian politics. She noted that all of the discussion about successors could be forgotten, and that the power will be in the Prime Minister's office once Putin moves there.

According to her, Putin has been building a parallel power structure for some time and will use it to suck the air out of the vertical of power which was one of the main accomplishments of his time in office. Putin will inevitably have to undermine the presidency if he wishes to remain preeminent on the Russian political scene.

I would disagree with this analysis on a couple of points. While the immediate question seems to be settled on the surface(understanding, of course, that he could always change his mind), there is much that remains unsettled both in the immediate term and in the long term. Yes, it seems as if the Medvedev vs. Ivanov question is resolved, as neither one seems to fit comfortably into "Putin's Plan." Zubkov, on the other hand, is a perfect fit as an aging bureaucrat who is known to be loyal to Putin. That said, it's interesting to note that at the end of the day, Putin could not trust either of the men whom he had supposedly been grooming. To be specific, he could not trust that either Ivanov or Medvedev would perform the role he intended them to perform and allow him to perform his desired role once he leaves office. In other words, by engineering his "plan" around a technocrat and his future position as Prime Minister, Putin's moves suggest that both potential heirs were still too independent for Putin's tastes.

But does this really settle the question? Are all the interesting questions and mysteries really put to rest? Between now and March 2008, it is possible that they are. The script has been revealed, and it is likely that it will be followed more or less according to the director's wishes.

However, the long-term implications of "Putin's Plan" have yet to be understood. In the first place, while Zubkov is assumed to be a pliable Putin loyalist, did not Yeltsin & Berezovsky not assume the same of Putin? While an independent Zubkov would no doubt face much greater hurdles to asserting his own power than did Putin in his early days as president, it's possible that he could. And while the probability of success would be low for Zubkov in such a scenario, in the very least it would produce some political fireworks: the constitutionally-elected president exercising his power to dismiss the prime minister, but the PM refuses to leave because he's the one with the informal power. All of a sudden Russia starts to look like Ukraine.... This is not to say that this will happen, or is even very likely. But it is possible, and it is an unknown.

The other assertion of Lyndon's panelist that I disagree with is the assumption that Putin will suck institutional power from the vertical he built and rebuild it in the Prime Minister's office. While this is possible, it doesn't serve Putin's longer-term interests if he seeks a return to the presidency in 2012 (or sooner, should Zubkov resign before then). Putin's challenge will be to maintain the formal institutions ("institutions" in political science jargon means "rules") as they are now while maximizing his power through informal institutions in the meantime. Thus, unless he envisions a permanent transformation of the Russian political system and its formal institutions whereby the president becomes a figurehead, he will not have an incentive to totally undermine the presidency if he has long time horizons.

Furthermore, it is important to ask whether the significance of his announcement lies in the possibility of him becoming Prime Minister, or whether the significance lies in his position (symbolic or formal) at the head of the United Russia party. If major political decisions can only be taken with the approval of the head of the Party who can deliver votes in the Duma, it may matter less who is the Prime Minister. Or, this may be the beginning of a tradition whereby the head of United Russia is always made Prime Minister. In either case, it is important to keep an eye on Putin's relationship with United Russia, as I have a feeling that is where his new power base will be located.

Ultimately, the biggest unknowns and the most consequential issues for the long term are the major institutional questions being shaped today. Political stability is brought by the iterated functioning of institutions (or rules), whether formal or informal. Democracies are stable because every X number of years the president or prime minister is selected according to rules which have been followed during that and previous iterations. And the most stable authoritarian regimes over time are those that have institutionalized the procedure for succession of leaders and have followed the same rules of succession repeatedly. Political instability, on the other hand, is brought about by a constant changing of the rules, or by actors refusing to follow the rules.

Thus, "Putin's Plan," while perhaps serving his immediate interest in maintaining power, might not be the optimal plan for the future survival and success of the regime, be it authoritarian or democratic. If Russia truly were a democratic country, then democracy would be stabilized by repeated elections whereby candidates are elected in contested, free, and fair elections. But Russia has yet to experience a "normal" transition of power, so the current institutional upheaval in the very least delays any kind of institutional stabilization.

Similarly, a non or partially-democratic Russia would be stabilized by iterated successions according to a common set of rules. It is possible that this is the beginning of such a process of institution building and that Putin has thought this far ahead. Nevertheless, Putin's shifting back and forth between offices would undermine the institutional stability of the regime in the long run. Assuming Putin intends to return to the presidency in 2012, then the 2008 "model" would be discarded and a new set of 2012 rules would be established. Similarly, power would once again return to the presidency. 2020 would then potentially bring a similar problem In other words, if power is shifting from the presidency to the premiership and back every 4-8 years, the overal institutional (and by extension political) stability of the regime is undermined.

As such, it is in the regime's long-term interest to institutionalize power within the presidency and amend the consititution to allow presidents to serve as long as they wish. The other option is to insitutionalize power in the office of the Prime Minister or the head of the United Russia party and keep it there. Shifting power back and forth is not good for stable authoritarian regimes. Now, note that I'm not advocating either of these options as normatively desirable - on the contrary, I'd like to see Russia hold open, democratic presidential elections, and I'm in favor of term limits. But my point is that from the perspective of the long-term survival of regime itself, it is better to establish rules and follow them.

Put another way, it is better for power to be institutionalized in the office rather than in the individual, even in an authoritarian regime. That way, when the individual dies the regime survives. But in order to have repeated successions, the incumbents must leave office (whether horizontally or vertically is less important) on a regular basis. His youth and vigor thus suggest that a "healthy" locus of power in the office rather than the person is unlikely as long as Putin is alive and well. Similarly, extreme personal authority amassed by a single individual is risky because nobody is allowed to develop the same kind of authority while the leader is alive. At the time of the leader's death, then, no successors have the political authority to rule that the predecessor did (think Stalin). While the regime might not be threatened, it will likely be stabilized.

And so, it turns out that "Putin's Plan" may not really be "Russia's Victory," even as Putin defines it. But at the end of the day, this is all speculation because - surprise surprise - we still don't really know where Russia is going and why it's going there...

02 October 2007

24 September 2007

The Sound of Marching Boots...

It takes a lot to bring me out of semi-retirement. Especially considering that I have far more important things to do, like writing a dissertation. (OK, in the big picture I realize that my dissertation isn't all that important). It takes even more to get me to write about current Russian events, but when this story passed across my desk this morning it sent chills so far down my spine that I could not help noting it on the blog.

The story came from the September 24, 2007 edition of the Moscow Times and can be found (at least temporarily) here. The headline announces, "Nashi Brigades to Enforce Public Order." I won't get into the background and history of Nashi, as there are others who have already done that quite well. You might want to check out Sean's Russia Blog, which has some outstanding coverage of Russian youth organizations.

The pro-Kremlin youth organization, Nashi ("Ours"), has recently begun organizing volunteer patrol brigades to help "enforce public order." While some might argue that this is simply a large-scale form of the "neighborhood watch," there is plenty of evidence to suggest that something more sinister is lurking below the surface. Or at least the potential for something sinister.

Consider the following choice quotes from Nashi activists which appeared in the Moscow Times article:

*"'In December, volunteers will head out on their own to patrol the streets and help Moscow police to control the situation,' Nashi said in a statement posted on its web site."

*"We are taking a civic-minded position," Lobkov said outside the library. "We don't know what the opposition will plan, so we have to be ready."

*[The opposition movement "Other Russia"] plans to hold a Dissenters' March in central Moscow on Oct. 7 and hopes to attract 5,000. "It's no secret" that the Nashi patrols will be mobilized for the opposition rally, Lobkov said. Asked separately what specific threats the patrols would head off, teenage Nashi activists Svetlana, Yegor and Anastasia gave identical answers. "The opposition wants to destabilize Russia," each of them answered.

*A city law on the patrols allows volunteers to "take physical action" if a lawbreaker is "actively disobedient" or resists. The law allows force as a last resort and "within the boundaries of the right to necessary defense." Lobkov, however, said Nashi activists would not use physical force, a position echoed by city police spokeswoman Alevtina Belousova.

*"We will carry out appropriate countermeasures should our opponents take to the streets" said television personality Ivan Demidov, a leader of Young Guard, the youth wing of the pro-Kremlin party United Russia.

Perhaps most disturbing about these quotes and the movement they represent is the fact that these activists view opposition - any opposition - as destabilizing. Opposition to the Kremlin, they believe, is a threat to the state and to Russia. Their desire is not to tolerate competition in the "marketplace of ideas" that is characteristic of a liberal democratic society, but rather to control the spread of ideas which contradict their own. In other words, they are engaging in a policy of containment. Opposition to the Kremlin is a threat which must be contained. The disturbing part of all of this, of course, is the fact that under a functioning democracy opposition is viewed as not only desirable but absolutely necessary. A democracy without opposition is not much of a democracy at all! That opposition should be viewed as an evil threat which must be contained speaks volumes of the Nashistis' understanding of democracy and politics in general.

Disturbing as this might be, it has even greater implications for the future of Russia's political development. One key characteristic of any democratic regime is the presence of multiple centers of political power. In other words, a variety of institutions, organizations, and structures that operate independently to exert political power. This might include the traditional "checks and balances" of the American system, but it extends to other realms outside the traditional three brances of government (Executive, Legislative, and Judicial). For example, civic organizations can influence the political process, as can political parties, regional and local leaders, the media, even business people. Like it or not, lobbyists too are independent centers that exert influence on the political system and thus weild some form of political power.

The point of all of this is that under democracy there is a plurality of actors who can affect the political process. One of the defining characteristics of Putin's Russia, on the other hand, has been the gradual reduction in the number of politically influential spheres. One by one the independent centers of political power have had their wings clipped by a strengthening Kremlin. The president selects members of the Federation Council and governors. The elimination of single-member districts from the Duma electoral system make it literally impossible for independent politicians to serve in the Duma. The raising of the representation barrier in Duma elections from 5% to 7% has reduced the number of parties that are represented in the Duma. The marshalling of state resources for the benefit of United Russia has both weakened opposition parties while making the Duma itself a pliant extension of the Kremilin's arm. Independent nationwide media has come under government control while big business and the oligarchs who run them have been taught a valuable lesson by the example of Mikhail Khodorkovsky. NGOs and civil society organizations have been burdened by complicated re-registration procedures while sometimes facing the threat of being branded an "extremist organization" subject to liquidation. In short, there are fewer and fewer actors that can exert any sort of political influence, let alone serve as a viable opposition.

As independent political centers are reduced, ordinary citizens are left with fewer and fewer means by which they can make their views known and influence the politics of their country. There comes a point at which their views can be expressed in the only place left open and unregulated: the streets. Thus, rallies, demonstrations, and protests are the last stand for those who wish to influence the politics of an authoritarianizing regime. It is no coincidence that as Putin's Russia has become more autocratic we've seen an increase in the number, frequency, and intensity of political protests. Nothing else can capture the attention of the regime, and it is now clear that the Kremlin's attention has been captured.

It is also clear now why Nashi and its Kremlin backers are so fearful of opposition and see the need to enforce order: public protests are the last means by which their power and control are threatened, and it is a threat which - like the Duma, the Federation Council, political parties, independent media, civic organizations, and oligarchs - must be contained. Russia's leaders have stated on several occasions that an "Orange Revolution" will not take place in Russia. Nashi's activists seem determined to make sure of it.

And so, come this fall, the Nashisti will take to the streets in massive numbers to "carry out appropriate countermeasures" against the fifth column of Russian society, the democratic opposition. What is frightening is the language Nashi is using - this is the language of battle, the language of warfare. Though they deny that they will use physical force, they are permitted by law to use force if an individual is actively disobedient. Thus, any refusal to comply with a Nashi activist's instructions could be construed as active disobedience and worthy of physical force. While they may claim that no force will be used, this is hardly a credible claim from an organization that casts its mission on the streets in the language of violence. In the heat of "battle" do we really expect the Nashi brigades to maintain the discipline to refrain from using physical force? Certainly not. Nor can we expect oversight or justice for those who are injured at the hands of a Nashi activist "maintaining order." Can one really imagine the police taking the word of an opposition protester over that of a Nashi patriot?

And so, we have many new sounds to look forward to this fall in Russia: the sounds of boots marching in step, the sounds of skulls cracking on pavement, and perhaps most troubling, the sound of the final nail being pounded into the coffin of public protest and democratic opposition.

The story came from the September 24, 2007 edition of the Moscow Times and can be found (at least temporarily) here. The headline announces, "Nashi Brigades to Enforce Public Order." I won't get into the background and history of Nashi, as there are others who have already done that quite well. You might want to check out Sean's Russia Blog, which has some outstanding coverage of Russian youth organizations.

The pro-Kremlin youth organization, Nashi ("Ours"), has recently begun organizing volunteer patrol brigades to help "enforce public order." While some might argue that this is simply a large-scale form of the "neighborhood watch," there is plenty of evidence to suggest that something more sinister is lurking below the surface. Or at least the potential for something sinister.

Consider the following choice quotes from Nashi activists which appeared in the Moscow Times article:

*"'In December, volunteers will head out on their own to patrol the streets and help Moscow police to control the situation,' Nashi said in a statement posted on its web site."

*"We are taking a civic-minded position," Lobkov said outside the library. "We don't know what the opposition will plan, so we have to be ready."

*[The opposition movement "Other Russia"] plans to hold a Dissenters' March in central Moscow on Oct. 7 and hopes to attract 5,000. "It's no secret" that the Nashi patrols will be mobilized for the opposition rally, Lobkov said. Asked separately what specific threats the patrols would head off, teenage Nashi activists Svetlana, Yegor and Anastasia gave identical answers. "The opposition wants to destabilize Russia," each of them answered.

*A city law on the patrols allows volunteers to "take physical action" if a lawbreaker is "actively disobedient" or resists. The law allows force as a last resort and "within the boundaries of the right to necessary defense." Lobkov, however, said Nashi activists would not use physical force, a position echoed by city police spokeswoman Alevtina Belousova.

*"We will carry out appropriate countermeasures should our opponents take to the streets" said television personality Ivan Demidov, a leader of Young Guard, the youth wing of the pro-Kremlin party United Russia.

Perhaps most disturbing about these quotes and the movement they represent is the fact that these activists view opposition - any opposition - as destabilizing. Opposition to the Kremlin, they believe, is a threat to the state and to Russia. Their desire is not to tolerate competition in the "marketplace of ideas" that is characteristic of a liberal democratic society, but rather to control the spread of ideas which contradict their own. In other words, they are engaging in a policy of containment. Opposition to the Kremlin is a threat which must be contained. The disturbing part of all of this, of course, is the fact that under a functioning democracy opposition is viewed as not only desirable but absolutely necessary. A democracy without opposition is not much of a democracy at all! That opposition should be viewed as an evil threat which must be contained speaks volumes of the Nashistis' understanding of democracy and politics in general.

Disturbing as this might be, it has even greater implications for the future of Russia's political development. One key characteristic of any democratic regime is the presence of multiple centers of political power. In other words, a variety of institutions, organizations, and structures that operate independently to exert political power. This might include the traditional "checks and balances" of the American system, but it extends to other realms outside the traditional three brances of government (Executive, Legislative, and Judicial). For example, civic organizations can influence the political process, as can political parties, regional and local leaders, the media, even business people. Like it or not, lobbyists too are independent centers that exert influence on the political system and thus weild some form of political power.

The point of all of this is that under democracy there is a plurality of actors who can affect the political process. One of the defining characteristics of Putin's Russia, on the other hand, has been the gradual reduction in the number of politically influential spheres. One by one the independent centers of political power have had their wings clipped by a strengthening Kremlin. The president selects members of the Federation Council and governors. The elimination of single-member districts from the Duma electoral system make it literally impossible for independent politicians to serve in the Duma. The raising of the representation barrier in Duma elections from 5% to 7% has reduced the number of parties that are represented in the Duma. The marshalling of state resources for the benefit of United Russia has both weakened opposition parties while making the Duma itself a pliant extension of the Kremilin's arm. Independent nationwide media has come under government control while big business and the oligarchs who run them have been taught a valuable lesson by the example of Mikhail Khodorkovsky. NGOs and civil society organizations have been burdened by complicated re-registration procedures while sometimes facing the threat of being branded an "extremist organization" subject to liquidation. In short, there are fewer and fewer actors that can exert any sort of political influence, let alone serve as a viable opposition.

As independent political centers are reduced, ordinary citizens are left with fewer and fewer means by which they can make their views known and influence the politics of their country. There comes a point at which their views can be expressed in the only place left open and unregulated: the streets. Thus, rallies, demonstrations, and protests are the last stand for those who wish to influence the politics of an authoritarianizing regime. It is no coincidence that as Putin's Russia has become more autocratic we've seen an increase in the number, frequency, and intensity of political protests. Nothing else can capture the attention of the regime, and it is now clear that the Kremlin's attention has been captured.

It is also clear now why Nashi and its Kremlin backers are so fearful of opposition and see the need to enforce order: public protests are the last means by which their power and control are threatened, and it is a threat which - like the Duma, the Federation Council, political parties, independent media, civic organizations, and oligarchs - must be contained. Russia's leaders have stated on several occasions that an "Orange Revolution" will not take place in Russia. Nashi's activists seem determined to make sure of it.

And so, come this fall, the Nashisti will take to the streets in massive numbers to "carry out appropriate countermeasures" against the fifth column of Russian society, the democratic opposition. What is frightening is the language Nashi is using - this is the language of battle, the language of warfare. Though they deny that they will use physical force, they are permitted by law to use force if an individual is actively disobedient. Thus, any refusal to comply with a Nashi activist's instructions could be construed as active disobedience and worthy of physical force. While they may claim that no force will be used, this is hardly a credible claim from an organization that casts its mission on the streets in the language of violence. In the heat of "battle" do we really expect the Nashi brigades to maintain the discipline to refrain from using physical force? Certainly not. Nor can we expect oversight or justice for those who are injured at the hands of a Nashi activist "maintaining order." Can one really imagine the police taking the word of an opposition protester over that of a Nashi patriot?

And so, we have many new sounds to look forward to this fall in Russia: the sounds of boots marching in step, the sounds of skulls cracking on pavement, and perhaps most troubling, the sound of the final nail being pounded into the coffin of public protest and democratic opposition.

05 September 2007

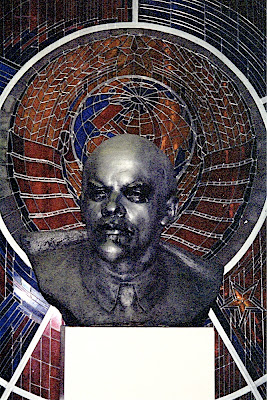

Comrade Lenin is Always With Us

Lest anyone think that I have disappeared from the face of the earth completely since returning to the United States, I am pleased to present what I hope is evidence to the contrary. Unfortunately, this evidence also proves that I've done very little productive work since my repatriation. However, I hope those of you still reading enjoy the fruits of my labor:

Behold, the online gallery of the entire Lenin bust collection. Bet you didn't know there were so many out there!

Thanks to the "no Lenins in the bedroom" rule (her rule, not mine), they are confined to the "Lenin Room" which also doubles as a study and triples as a guest room. For better or worse, nobody yet seems willing to stay with us as a guest. As if there's something weird about sleeping under the watchful gaze of 37 pairs of Lenin eyes...

Oh, and I suppose the "Lenin Room" also serves as the "pickle room," as it seems to be a suitable place for the 16 pounds of Russian dill pickles I'm fermenting at the moment. But more on that later...

25 July 2007

New Horizons

Well, that day is finally here. I'm going home today. Or at least I think I'm going home today. When leaving Russia I have a policy of never making definitive declarations until the plane has lifted off. But to be on the safe side, I never celebrate until the plane touches down on American soil. After all, it's better not to get your hopes up in case Russia decides to have one of her "moments" right at the time you think you are leaving.

I'm too deeply embedded in my experience here to be able to reflect on it properly at the moment. Besides, I haven't finished packing the Lenins either. So reflections will have to wait a bit.

Of course, this brings up the question of the future of this blog. On the one hand, the blog isn't much without Russia's participation. She has provided all the material, while I simply relay it to a (semi) captivated audience. I somehow doubt that "My Life" from a sleepy college town will be quite so intriguing as dogs that ride the metro. Or pickles. I suppose I could convert to Russia punditism and comment on more contemporary political issues, but there are plenty of people doing that already. Plus, I have a dissertation to get writing.

But not to despair. I do still have a few stories waiting in reserve and I hope to put them on (digital) paper eventually. For example, I never got around to writing about the vendors on Arbat that assault you with "fyuh khats from reeel minks!" ("fur hats from real mink," except it's really muskrat, not mink). Or the guillotine doors of metro cars that put the French Revolution to shame. And the metro turnstile barrier that almost preemtively took the life of my unborn child (if you've been to Moscow, you know what I mean). Oh, plus there's Russia's magically soft roads - so soft and cushy that cab drivers insist that seatbelts are unnecessary.

But even better than these memories from the past is the promise of future stories. It turns out that (for better or for worse) I've received funding to do research for about 6 months next year in Ukraine and Belarus. So, starting in April 2008 Darkness at Noon will begin broadcasting live from Kiev and Minsk. If the Ukrainians and Belarussians are anything like their wacky Russian bretheren, there are sure to be some good stories coming down the line...

In the meantime, check back here occasionally, as I'm sure I'll have some stories about the wonderful process of obtaining a visa to Belarus. Eh, how hard can it be?

In closing, let me just thank all of you who have been dedicated (and semi-dedicated) readers over the past several months. While I don't seek out trouble, there are more than a few occasions when I pushed my boundaries and went a little farther than I'm used to so that I would have something to write for you. I have no doubt that I'm a better person for it and my experiences were that much richer for it. So thanks for prodding me into dark corners and sharing the adventures that come of it.

Oh, and I'd also like to thank all the people who arrive here via Google looking for "Lenins n Things." You have inflated my counter statistics beyond my wildest dreams. I hope you found what you were looking for.

До скорого,

R

I'm too deeply embedded in my experience here to be able to reflect on it properly at the moment. Besides, I haven't finished packing the Lenins either. So reflections will have to wait a bit.

Of course, this brings up the question of the future of this blog. On the one hand, the blog isn't much without Russia's participation. She has provided all the material, while I simply relay it to a (semi) captivated audience. I somehow doubt that "My Life" from a sleepy college town will be quite so intriguing as dogs that ride the metro. Or pickles. I suppose I could convert to Russia punditism and comment on more contemporary political issues, but there are plenty of people doing that already. Plus, I have a dissertation to get writing.

But not to despair. I do still have a few stories waiting in reserve and I hope to put them on (digital) paper eventually. For example, I never got around to writing about the vendors on Arbat that assault you with "fyuh khats from reeel minks!" ("fur hats from real mink," except it's really muskrat, not mink). Or the guillotine doors of metro cars that put the French Revolution to shame. And the metro turnstile barrier that almost preemtively took the life of my unborn child (if you've been to Moscow, you know what I mean). Oh, plus there's Russia's magically soft roads - so soft and cushy that cab drivers insist that seatbelts are unnecessary.

But even better than these memories from the past is the promise of future stories. It turns out that (for better or for worse) I've received funding to do research for about 6 months next year in Ukraine and Belarus. So, starting in April 2008 Darkness at Noon will begin broadcasting live from Kiev and Minsk. If the Ukrainians and Belarussians are anything like their wacky Russian bretheren, there are sure to be some good stories coming down the line...

In the meantime, check back here occasionally, as I'm sure I'll have some stories about the wonderful process of obtaining a visa to Belarus. Eh, how hard can it be?

In closing, let me just thank all of you who have been dedicated (and semi-dedicated) readers over the past several months. While I don't seek out trouble, there are more than a few occasions when I pushed my boundaries and went a little farther than I'm used to so that I would have something to write for you. I have no doubt that I'm a better person for it and my experiences were that much richer for it. So thanks for prodding me into dark corners and sharing the adventures that come of it.

Oh, and I'd also like to thank all the people who arrive here via Google looking for "Lenins n Things." You have inflated my counter statistics beyond my wildest dreams. I hope you found what you were looking for.

До скорого,

R

12 July 2007

Some Lenins I've Known

I thought it would be a good idea to sift through 7 years-worth of photos I've taken in Russia and her neighbors and put up an album of some of the best Lenin statues I've photographed. Some of the photos pre-date digital cameras and are a little old/grainy looking, but you get the picture (pun intended?) So here they are...

Finland Station, St. Petersburg:

From this angle, Lenin gives you a thumbs-up: "Hey, isn't revolution GREAT?!!"

Lenin with entourage at Oktyabrskaya Square, Moscow:

Lenin guarding the grounds at VDNKh:

He looks lost in thought. Probably thinking about getting a tasty shaurma from one of the nearby vendors:

Lenin at Sergiev Pasad, paradoxically former seat of the Russian Orthodox Church:

This Lenin stood next to the old Gorbushka, back when it was a sprawling outdoor bazaar. Someone has spray painted "John Lennon" on the base. I've never been able to find this Lenin again, though it probably doesn't help that I've never tried:

Inside the Central Armed Forces Museum in Moscow. As this one is marble, it would be VERY expensive to ship home, I think:

At the outdoor sculplture park next to the New Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow:

Inside the WWII museum in Minsk:

Also in Minsk:

Lenin pointing at Japan from Vladivostok: "Hey! Does that sushi stuff come with mayonnaise?"

In Volgograd (Stalingrad), Lenin says, "See how nice it is now that we've rebuilt our city?"

The largest bust of Lenin in the world, located in Ulan Ude. I'll confess that this is not my picture. When I was there, it was the middle of the night, it was December, I was sick, and only halfway through my trip on the Trans-Siberian. Needless to say, my own photos didn't turn out very good...

Tambov: Reverend Lenin says, "Can I get an AMEN!"

In Lipetsk, Comrade Lenin doesn't say much. There's hardly any traffic through Lenin Square (recently renamed Cathedral Square because there's a, um, cathedral there). I think he gets lonely.

In Nizhny Novgorod, Lenin says, "Look at the wonderful shopping mall they've built next to me. Maybe I was wrong about this whole 'capitalism is evil thing...'"

For the most comprehensive archive of Lenin monuments in Russia, the former Soviet Union, and around the world, take a look at monulent.ru (in Russian), which has Lenin monuments organized by city. Bet you never knew there were so many!

Finland Station, St. Petersburg:

From this angle, Lenin gives you a thumbs-up: "Hey, isn't revolution GREAT?!!"

Lenin with entourage at Oktyabrskaya Square, Moscow:

Lenin guarding the grounds at VDNKh:

He looks lost in thought. Probably thinking about getting a tasty shaurma from one of the nearby vendors:

Lenin at Sergiev Pasad, paradoxically former seat of the Russian Orthodox Church:

This Lenin stood next to the old Gorbushka, back when it was a sprawling outdoor bazaar. Someone has spray painted "John Lennon" on the base. I've never been able to find this Lenin again, though it probably doesn't help that I've never tried:

Inside the Central Armed Forces Museum in Moscow. As this one is marble, it would be VERY expensive to ship home, I think:

At the outdoor sculplture park next to the New Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow:

Inside the WWII museum in Minsk:

Also in Minsk:

Lenin pointing at Japan from Vladivostok: "Hey! Does that sushi stuff come with mayonnaise?"

In Volgograd (Stalingrad), Lenin says, "See how nice it is now that we've rebuilt our city?"

The largest bust of Lenin in the world, located in Ulan Ude. I'll confess that this is not my picture. When I was there, it was the middle of the night, it was December, I was sick, and only halfway through my trip on the Trans-Siberian. Needless to say, my own photos didn't turn out very good...

Tambov: Reverend Lenin says, "Can I get an AMEN!"

In Lipetsk, Comrade Lenin doesn't say much. There's hardly any traffic through Lenin Square (recently renamed Cathedral Square because there's a, um, cathedral there). I think he gets lonely.

In Nizhny Novgorod, Lenin says, "Look at the wonderful shopping mall they've built next to me. Maybe I was wrong about this whole 'capitalism is evil thing...'"

For the most comprehensive archive of Lenin monuments in Russia, the former Soviet Union, and around the world, take a look at monulent.ru (in Russian), which has Lenin monuments organized by city. Bet you never knew there were so many!

07 July 2007

Petersburg White Nights

Here's a few more pictures from my recent trip to St. Petersburg. These were taken between 11:00 pm and 1:00 am. For someone who grew up in a place where 9:00 is the latest the sun ever sets in the summer, seeing it still light out at midnight is a bizarre experience.

The event I photographed was a concert and outdoor party thrown for the city's high school graduates, who had graduated that day. As you can see from the photos, there were hordes of kids everywhere. Nevsky Prospect was closed from Gostiniy Dvor all the way down to the river, and people were constantly streaming towards the Winter Palace.

I finally bailed at 1:00, partly because I was tired and partcly because it looked like things could easily get out of hand. People were starting to get drunk, rowdy, and pushy, and there were a few moments where someone smaller than I would have had a hard time holding their own against the pulsing crowd.

As I walked back up Nevsky Prospect, the masses continued to flow toward the concert. The street was full of broken glass - as people finished their beers, they would set the bottle on the side of the road. Sooner or later someone would trip over it or deliberately kick it and it would shatter on the pavement. Some of the ornamental iron bollards along Nevsky were ripped out of their foundations, often prying up the pavement stones with them.

To the credit of the St. Petersburg municipal services, by 9:00 the next morning the entire length of the street was spotless - all the glass had been removed and all the bollards and chains had been restored to their original positions (though some were tilting a bit precariously).

In any case, that's enough from me. Here are the pictures:

Guest appearance by St. Petersburg governor (and potential Putin dark-horse successor?) Valentina Matvienko:

This is my favorite photo: two lines (there's another one on the right that's not pictured) of OMON officers guarding..... an extension cord.

The event I photographed was a concert and outdoor party thrown for the city's high school graduates, who had graduated that day. As you can see from the photos, there were hordes of kids everywhere. Nevsky Prospect was closed from Gostiniy Dvor all the way down to the river, and people were constantly streaming towards the Winter Palace.

I finally bailed at 1:00, partly because I was tired and partcly because it looked like things could easily get out of hand. People were starting to get drunk, rowdy, and pushy, and there were a few moments where someone smaller than I would have had a hard time holding their own against the pulsing crowd.

As I walked back up Nevsky Prospect, the masses continued to flow toward the concert. The street was full of broken glass - as people finished their beers, they would set the bottle on the side of the road. Sooner or later someone would trip over it or deliberately kick it and it would shatter on the pavement. Some of the ornamental iron bollards along Nevsky were ripped out of their foundations, often prying up the pavement stones with them.

To the credit of the St. Petersburg municipal services, by 9:00 the next morning the entire length of the street was spotless - all the glass had been removed and all the bollards and chains had been restored to their original positions (though some were tilting a bit precariously).

In any case, that's enough from me. Here are the pictures:

Guest appearance by St. Petersburg governor (and potential Putin dark-horse successor?) Valentina Matvienko:

This is my favorite photo: two lines (there's another one on the right that's not pictured) of OMON officers guarding..... an extension cord.

03 July 2007

Soviet Jokes

In looking for the Lenin triple-wide joke, I came across the following site that is loaded with tons of classic Soviet-era jokes (translated into English), organized by theme. This should keep you all busy (and laughing) for at least a few days...

Laughing Under the Covers

Enjoy!

(PS - the above cartoon is the Pulizer-prize winning work of Jim Borgman...)

Laughing Under the Covers

Enjoy!

(PS - the above cartoon is the Pulizer-prize winning work of Jim Borgman...)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)